Is the Most Elaborate Church of the Golden Age of Byzantine Art

| From left to right: Hagia Sophia in Turkey, Basilica of San Vitale in Italia, Church of St John the Baptist in Crimea, Basilica of San Vitale | |

| Years active | quaternary century – 1453 |

|---|---|

Byzantine architecture is the compages of the Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire.

The Byzantine era is usually dated from 330 Advertisement, when Constantine the Great moved the Roman capital to Byzantium, which became Constantinople, until the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453. Yet, there was initially no hard line betwixt the Byzantine and Roman empires, and early on Byzantine architecture is stylistically and structurally indistinguishable from earlier Roman architecture. This terminology was introduced by modern historians to designate the medieval Roman Empire equally it evolved as a distinct creative and cultural entity centered on the new capital of Constantinople (modern-24-hour interval Istanbul) rather than the city of Rome and its surround.

Its architecture dramatically influenced the afterwards medieval architecture throughout Europe and the Most East, and became the principal progenitor of the Renaissance and Ottoman architectural traditions that followed its collapse.

Characteristics [edit]

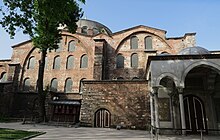

Pammakaristos Church, as well known every bit the Church of Theotokos Pammakaristos (Greek: Θεοτόκος ἡ Παμμακάριστος, "All-Blessed Female parent of God"), is one of the most famous Greek Orthodox Byzantine churches in Istanbul

When the Roman Empire became Christian (later on having extended eastwards) with its new capital at Constantinople, its architecture became more sensuous and aggressive. This new manner with exotic domes and richer mosaics would come to exist known as "Byzantine" before information technology traveled westward to Ravenna and Venice and equally far n as Moscow. Well-nigh of the churches and basilicas have high-riding domes, which created vast open spaces at the centers of churches, thereby heightening the calorie-free. The circular arch is a fundamental of Byzantine way. Magnificent golden mosaics with their graphic simplicity brought light and warmth into the center of churches. Byzantine capitals break away from the Classical conventions of ancient Greece and Rome with sinuous lines and naturalistic forms, which are precursors to the Gothic manner.

The richest interiors were finished with thin plates of marble or stone. Some of the columns were too made of marble. Other widely used materials were bricks and stone.[1] Mosaics made of stone or drinking glass tesserae were too elements of interior architecture. Precious woods furniture, like beds, chairs, stools, tables, bookshelves and silver or gilt cups with cute reliefs, decorated Byzantine interiors.[ii]

In the aforementioned way the Parthenon is the most impressive monument for Classical faith, Hagia Sophia remained the iconic church for Christianity. The temples of these 2 religions differ essentially from the signal of view of their interiors and exteriors. For Classical temples, only the outside was important, because only the priests entered the interior, where the statue of the deity to whom the temple was dedicated was kept. The ceremonies were held outside, in front end of the temple. Instead, Christian liturgies were held inside the churches.[3]

Columns [edit]

Byzantine columns are quite varied, more often than not developing from the classical Corinthian, but tending to have an even surface level, with the ornamentation undercut with drills. The block of stone was left rough as it came from the quarry, and the sculptor evolved new designs to his own fancy, and so that one rarely meets with many repetitions of the aforementioned blueprint. One of the near remarkable designs features leaves carved as if blown by the air current; the finest example being at the 8th-century Hagia Sophia (Istanbul). Those in the Cathedral of Saint Mark, Venice (1071) specially attracted John Ruskin's fancy. Others appear in Sant'Apollinare in Classe, Ravenna (549).

The column in San Vitale, Ravenna (547) shows above information technology the dosseret required to behave the curvation, the springing of which was much wider than the abacus of the column. On eastern columns the eagle, the lion and the lamb are occasionally carved, merely treated conventionally.

There are ii types of columns used at Hagia Sophia: Composite and Ionic. The Composite cavalcade that emerged during the Tardily Byzantine Empire, mainly in Rome, combines the Corinthian with the Ionic. Composite columns line the principal space of the nave. Ionic columns are used behind them in the side spaces, in a mirror position relative to the Corinthian or Blended orders (as was their fate well into the 19th century, when buildings were designed for the first time with a monumental Ionic social club). At Hagia Sophia, though, these are non the standard majestic statements. The columns are filled with foliage in all sorts of variations. In some, the modest, lush leaves appear to be defenseless upwards in the spinning of the scrolls – conspicuously, a different, nonclassical sensibility has taken over the pattern.

The columns at Basilica of San Vitale show wavy and delicate floral patterns similar to decorations found on belt buckles and dagger blades. Their inverted pyramidal form has the await of a handbasket.

-

Illustration of a Byzantine Corinthian column

Overview of extant monuments [edit]

Early Byzantine architecture drew upon earlier elements of Greco-Roman compages. Stylistic migrate, technological advocacy, and political and territorial changes meant that a distinct style gradually resulted in the Greek cantankerous plan in church architecture.[4]

Buildings increased in geometric complication, brick and plaster were used in addition to stone in the ornament of of import public structures, classical orders were used more freely, mosaics replaced carved ornamentation, circuitous domes rested upon massive piers, and windows filtered lite through sparse sheets of alabaster to softly illuminate interiors. Most of the surviving structures are sacred, with secular buildings having been destroyed.

Early architecture [edit]

Prime number examples of early Byzantine architecture date from the Emperor Justinian I's reign and survive in Ravenna and Istanbul, as well equally in Sofia (the Church building of St Sophia).

One of the bully breakthroughs in the history of Western compages occurred when Justinian'southward architects invented a complex system providing for a smooth transition from a square programme of the church to a round dome (or domes) by means of pendentives.

In Ravenna, the longitudinal basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo, and the octagonal, centralized structure of the church of San Vitale, deputed past Emperor Justinian but never seen past him, was built. Justinian'due south monuments in Istanbul include the domed churches of Hagia Sophia and Hagia Irene, but there is also an earlier, smaller church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus (locally referred to as "Little Hagia Sophia"), which might have served as a model for both in that information technology combined the elements of a longitudinal basilica with those of a centralized building.

The 6th-century church building of Hagia Irene in Istanbul was substantially rebuilt after an convulsion in the 8th century.

Other structures include the ruins of the Swell Palace of Constantinople, the innovative walls of Constantinople (with 192 towers) and Basilica Cistern (with hundreds of recycled classical columns). A frieze in the Ostrogothic palace in Ravenna depicts an early Byzantine palace.

Hagios Demetrios in Thessaloniki, Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai, Jvari Monastery in nowadays-day Georgia, and three Armenian churches of Echmiadzin all date primarily from the 7th century and provide a glimpse on architectural developments in the Byzantine provinces post-obit the age of Justinian.

Remarkable technology feats include the 430 k long Sangarius Bridge and the pointed arch of Karamagara Bridge.

The period of the Macedonian dynasty, traditionally considered the epitome of Byzantine art, has not left a lasting legacy in compages. It is presumed that Basil I's votive church building of the Theotokos of the Pharos and the Nea Ekklesia (both no longer real) served as a model for most cantankerous-in-foursquare sanctuaries of the menstruum, including the Cattolica di Stilo in southern Italy (9th century), the monastery church building of Hosios Lukas in Greece (c. m), Nea Moni of Chios (a pet project of Constantine IX), and the Daphni Monastery near Athens (c. 1050).

The Hagia Sophia church in Ochrid (present-day North Republic of macedonia), congenital in the time of Boris I of Bulgaria, and the eponymous cathedral in Kiev (present-day Ukraine) testify to a vogue for multiple subsidiary domes set on drums, which would proceeds in pinnacle and narrowness with the progress of time.[ citation needed ]

Comnenian and Paleologan periods [edit]

In Istanbul and Asia Minor the architecture of the Komnenian menstruation is almost not-real, with the notable exceptions of the Elmali Kilise and other stone sanctuaries of Cappadocia, and of the Churches of the Pantokrator and of the Theotokos Kyriotissa in Istanbul. Nearly examples of this architectural style and many of the other older Byzantine styles only survive on the outskirts of the Byzantine world, equally most significant and aboriginal churches and buildings were in Asia Minor. During Globe State of war I, almost all churches that ended upward inside the Turkish borders were destroyed or converted into mosques. Some were abandoned as a result of the Greek and Christian genocides from 1915 to 1923. Similar styles can be constitute in countries such as North Macedonia, Bulgaria, Serbia, Republic of croatia, Russia and other Slavic lands, every bit well equally in Sicily (Cappella Palatina) and Veneto (St Mark'south Basilica, Torcello Cathedral).

The Paleologan period is well represented in a dozen former churches in Istanbul, notably St Saviour at Chora and St Mary Pammakaristos. Unlike their Slavic counterparts, the Paleologan architects never accented the vertical thrust of structures. As a event, the late medieval architecture of Byzantium (barring the Hagia Sophia of Trebizond) is less prominent in height.

The Church of the Holy Apostles (Thessaloniki) is cited every bit an archetypal construction of the belatedly period with its exterior walls intricately busy with complex brickwork patterns or with glazed ceramics. Other churches from the years immediately predating the fall of Constantinople survive on Mount Athos and in Mistra (e.thou. Brontochion Monastery). In Middle Byzantine architecture "cloisonné masonry" refers to walls built with a regular mix of stone and brick, frequently with more than of the latter. The 11th or 12th-century Pammakaristos Church in Istanbul is an example.[5]

Structural evolution [edit]

The geometric conception of the Hagia Sophia is based on mathematical formulas of Heron of Alexandria. Information technology avoids employ of irrational numbers for square diagonals and circle circumferences and contrieves thus a highly elaborated mathematical space

As early every bit the building of Constantine's churches in Palestine there were 2 chief types of plan in utilise: the basilican, or axial, type, represented past the basilica at the Holy Sepulchre, and the circular, or central, type, represented past the great octagonal church once at Antioch.

The St. George Rotunda; some remains of Serdica can be seen in the foreground

Those of the latter type nosotros must suppose were nearly always vaulted, for a fundamental dome would seem to furnish their very purpose. The central space was sometimes surrounded by a very thick wall, in which deep recesses, to the interior, were formed, equally at Church of St. George, Sofia, congenital by the Romans in the 4th century as a cylindrical domed structure built on a foursquare base, and the noble Church of Saint George, Thessaloniki (5th century), or by a vaulted aisle, as at Santa Costanza, Rome (4th century); or annexes were thrown out from the central space in such a way as to form a cross, in which these additions helped to counterpoise the central vault, as at the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, Ravenna (5th century). The most famous church building of this type was that of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople. Vaults appear to take been early applied to the basilican type of plan; for instance, at Hagia Irene, Constantinople (6th century), the long body of the church is covered past ii domes.

Interior of the Hagia Sophia under renovation, showing many features of the grandest Byzantine architecture.

At Saint Sergius, Constantinople, and San Vitale, Ravenna, churches of the central blazon, the space under the dome was enlarged by having apsidal additions made to the octagon. Finally, at Hagia Sophia (6th century) a combination was fabricated which is possibly the almost remarkable piece of planning ever contrived. A primal space of 100 ft (30 thou) foursquare is increased to 200 ft (60 m) in length by calculation two hemicycles to it to the east and the west; these are once again extended past pushing out three minor apses e, and ii others, one on either side of a straight extension, to the west. This unbroken expanse, about 260 ft (80 m) long, the larger part of which is over 100 ft (30 grand) wide, is entirely covered by a arrangement of domical surfaces. Above the conchs of the minor apses rise the two great semi-domes which cover the hemicycles, and between these bursts out the vast dome over the central foursquare. On the two sides, to the north and south of the dome, it is supported by vaulted aisles in two stories which bring the exterior form to a general square.

The apse of the church with cantankerous at Hagia Irene. Nearly all the decorative surfaces in the church building have been lost.

At the Holy Apostles (6th century) five domes were applied to a cruciform plan; the central dome was the highest. After the 6th century there were no churches built which in any way competed in calibration with these great works of Justinian, and the plans more or less tended to estimate to 1 type. The central expanse covered by the dome was included in a considerably larger square, of which the iv divisions, to the eastward, west, northward and southward, were carried up higher in the vaulting and roof system than the 4 corners, forming in this way a sort of nave and transepts. Sometimes the central space was square, sometimes octagonal, or at least there were eight piers supporting the dome instead of four, and the nave and transepts were narrower in proportion.

If we depict a foursquare and divide each side into three so that the heart parts are greater than the others, and then split up the area into nine from these points, we approximate to the typical setting out of a plan of this time. Now add three apses on the east side opening from the three divisions, and opposite to the west put a narrow entrance porch running correct across the forepart. Notwithstanding in front put a square courtroom. The court is the atrium and usually has a fountain in the middle under a canopy resting on pillars. The entrance porch is the narthex. Straight under the center of the dome is the ambo, from which the Scriptures were proclaimed, and beneath the ambo at flooring level was the place for the choir of singers. Across the eastern side of the cardinal square was a screen which divided off the bema, where the altar was situated, from the body of the church; this screen, bearing images, is the iconostasis. The altar was protected by a awning or ciborium resting on pillars. Rows of rising seats around the curve of the apse with the patriarch'south throne at the centre eastern point formed the synthronon. The 2 smaller compartments and apses at the sides of the bema were sacristies, the diaconicon and prothesis. The ambo and bema were connected by the solea, a raised walkway enclosed past a railing or low wall.

The continuous influence from the E is strangely shown in the fashion of decorating external brick walls of churches congenital about the 12th century, in which bricks roughly carved into form are ready then equally to make bands of ornamentation which it is quite clear are imitated from Cufic writing. This fashion was associated with the disposition of the exterior brick and stone work generally into many varieties of pattern, zig-zags, cardinal-patterns etc.; and, as similar ornamentation is plant in many Persian buildings, it is probable that this custom also was derived from the E. The domes and vaults to the outside were covered with lead or with tiling of the Roman diversity. The window and door frames were of marble. The interior surfaces were adorned all over by mosaics or frescoes in the higher parts of the edifice, and below with incrustations of marble slabs, which were often of very cute varieties, and disposed so that, although in i surface, the coloring formed a series of large panels. The better marbles were opened out and then that the ii surfaces produced by the division formed a symmetrical design.

Legacy [edit]

Chora Church medieval Byzantine Greek Orthodox church preserved every bit the Chora Museum in the Edirnekapı neighborhood of Istanbul

In the West [edit]

Ultimately, Byzantine architecture in the West gave way to Carolingian, Romanesque, and Gothic architecture. Simply a groovy office of electric current Italy used to belong to the Byzantine Empire before that. Nifty examples of Byzantine architecture are still visible in Ravenna (for instance Basilica di San Vitale which architecture influenced the Palatine Chapel of Charlemagne).

In the East [edit]

Every bit for the East, Byzantine architectural tradition exerted a profound influence on early Islamic architecture, especially Umayyad architecture. During the Umayyad Caliphate era (661-750), as far as the Byzantine impact on early Islamic architecture is concerned, the Byzantine arts formed a fundamental source to the new Muslim artistic heritage, especially in Syrian arab republic. At that place are considerable Byzantine influences which tin be detected in the distinctive early Islamic monuments in Syrian arab republic (709–715). While these give clear reference in programme - and somewhat in ornament - to Byzantine art, the plan of the Umayyad Mosque has also a remarkable similarity with sixth- and seventh-century Christian basilicas, but information technology has been modified and expanded on the transversal centrality and not on the normal longitudinal centrality as in the Christian basilicas. The tile piece of work, geometric patterns, multiple arches, domes, and polychrome brick and stone work that narrate Muslim and Moorish architecture were influenced heavily by Byzantine compages.

Post-Byzantine compages in Eastern Orthodox countries [edit]

In Bulgaria, North Macedonia, Serbia, Romania, Republic of belarus, Georgia, Ukraine, Russia and other Orthodox countries the Byzantine architecture persisted even longer, from the 16th upwards to the 18th centuries, giving nascence to local mail-Byzantine schools of architecture.

- in Medieval Bulgaria: The Preslav and Tarnovo architectural schools.

- In Medieval Serbia: Raška architectural schoolhouse, Vardar architectural school and Morava architectural school.

Neo-Byzantine compages [edit]

Neo-Byzantine compages was followed in the wake of the 19th-century Gothic revival, resulting in such jewels as Westminster Cathedral in London, and in Bristol from about 1850 to 1880 a related fashion known every bit Bristol Byzantine was popular for industrial buildings which combined elements of the Byzantine style with Moorish compages. Information technology was adult on a wide-scale basis in Russia during the reign of Alexander Ii by Grigory Gagarin and his followers who designed St Volodymyr's Cathedral in Kiev, St Nicholas Naval Cathedral in Kronstadt, Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Sofia, Saint Mark's church building in Belgrade and the New Athos Monastery in New Athos near Sukhumi. The largest Neo-Byzantine project of the 20th century was the Church of Saint Sava in Belgrade.

Important Byzantine monuments [edit]

Hagia Irene [edit]

One of the less famous Byzantine churches is Hagia Irene. This church served as a model church for the more famous church, Hagia Sophia. Construction on the church began in the quaternary century. This was the first church building that was built in Constantinople, only due to its location, it was severely damaged past earthquakes and the Nika riots, and required repair several times. The Hagia Irene is divers past its large atrium, and is in fact the only surviving building of the Byzantine Empire to take such a feature.[7]

Structure [edit]

Hagia Irene is composed mainly of 3 materials: rock, brick, and mortar. Bricks 70 cm ten 35 cm x 5 cm were used, and these bricks were glued together using mortar approximately 5 cm thick. The building materials called for the construction of the church had to be lightweight, durable, and strong. Volcanic materials were called for this purpose, as volcanic concrete is very low-cal and durable. Maybe the nearly definite feature of the Hagia Irene is the strict contrast between the interior and exterior design. While the evidently outside composed of stone and brick favors functionality, the interior is busy in elaborate mosaics, decorative marble, and, in some places, covered in plaster. Another important feature of the church include two domes that follow i behind another, the outset being a lower oval, and the second being a higher semi-circle.[7]

History of Hagia Irene [edit]

Throughout history Hagia Irene has undergone several changes. In that location were multiple repairs due to the Nika riots and earthquakes. When the Ottomans took over Hagia Irene they repurposed it and made a few changes, simply none equally desperate as what was done to Hagia Sophia.[7] Today, Hagia Irene is notwithstanding standing and open to visitors as a museum. It is open up everyday, except for Tuesdays.[8]

Structure of Hagia Irene

| Fourth dimension | Effect |

|---|---|

| 4th C. | Construction Began |

| 532 | Church building was burned during Nika revolt |

| 548 | Emperor Justinian repaired the church |

| 740 | Pregnant damages from earthquakes |

| 1453 | Constantinople was conquered by the Ottomans - became a weapons storehouse |

| 1700 | Became a museum |

| 1908-1978 | Served equally a war machine museum. |

Hagia Sophia [edit]

The almost famous example of Byzantine compages is the Hagia Sophia, and it has been described equally "property a unique position in the Christian globe",[ix] and every bit an architectural and cultural icon of Byzantine and Eastern Orthodox civilization.[10] [11] [9] The Hagia Sophia held the title of largest church in the globe until the Ottoman Empire sieged the Byzantine upper-case letter. Later on the fall of Constantinople, the church building was used by the Muslims for their religious services until 1931, when it was reopened as a museum in 1935. Translated from Greek, the proper noun Hagia Sophia means "Holy Wisdom".[12]

Construction of Hagia Sophia [edit]

Outside view of Hagia Sophia

The structure is a combination of longitudinal and key structures. This church was a role of a larger complex of buildings created past Emperor Justinian. This fashion influenced the structure of several other buildings, such as St. Peter'south Basilica. Hagia Sophia should take been congenital to withstand earthquakes, only since the construction of Hagia Sophia was rushed this technology was not implemented in the design, which is why the building has had to be repaired and then many times due to amercement from the earthquakes. The dome is the key feature of Hagia Sophia as the domed basilica is representative of Byzantine compages. Both of the domes collapsed at unlike times throughout history due to earthquakes and had to be rebuilt.[13]

History of Hagia Sophia [edit]

The original construction of Hagia Sophia was possibly ordered past Constantine, but ultimately carried out by his son Constantius II in 360. Constantine's building of churches, specifically the Hagia Sophia, was considered an incredibly meaning component in his shift of the centralization of power from Rome in the west to Constantinople in the east, and was considered the high-signal of religious and political celebration. The construction of the terminal version of the Hagia Sophia, which withal stands today, was overseen by Emperor Justinian. Between the rule of these two Emperors, Hagia Sophia was destroyed and rebuilt twice. Following its reconstruction, Hagia Sophia was considered the center of Orthodox Christianity for 900 years, until the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottomans.[14]

| Time | Event |

|---|---|

| 360 | Construction began |

| 404 | Hagia Sophia was burned down in public riot. |

| 415 | Construction begins on the next version of Hagia Sophia. |

| 532 | The church is once once more demolished during Nika revolts. |

| 537 | The final version of Hagia Sophia opens to Christian Worship subsequently five more years of construction. |

| 558 | Earthquake - dome complanate |

| 859 | Burn damage |

| 869 | Convulsion damage |

| 989 | More earthquake impairment |

| 1317 | Large buttresses added |

| 1453 | Constantinople is conquered past the Ottomans - converted into a Muslim place of worship |

| 1935 | Hagia Sophia is converted into a museum by secularists |

| 2020 | Reverted to a mosque |

Gallery [edit]

-

-

-

-

-

-

Agkistro Byzantine bathroom

-

See also [edit]

- Architectural way

- Architecture of the Tarnovo Artistic School

- Architecture of Kievan Rus'

- Byzantine art

- Golden Age of medieval Bulgarian civilisation

- History of Roman and Byzantine domes

- Medieval architecture

- Neo-Byzantine architecture

- Ottoman architecture

- Russian-Byzantine architecture

- Sasanian architecture

- Armenian architecture

References [edit]

- ^ Dimitriu Hurmuziadis, Lucia (1979). Cultura Greciei (in Romanian). Editura științifică și encyclopedică. p. 93.

- ^ Graur, Neaga (1970). Stiluri în arta decorativă (in Romanian). Cerces. p. 38.

- ^ Dimitriu Hurmuziadis, Lucia (1979). Cultura Greciei (in Romanian). Editura științifică și enciclopedică. p. 92.

- ^ "Byzantine architecture".

- ^ Darling, Janina K., Compages of Greece, p. xliii, 2004, Greenwood Press, ISBN 9780313321528, google books, a rather more restricted definition than some sources utilise.

- ^ Godlewski, Włodzimierz (2013). Dongola-aboriginal Tungul. Archaeological guide (PDF). Shine Heart of Mediterranean Archaeology, Academy of Warsaw. p. 12. ISBN978-83-903796-6-i.

- ^ a b c d Musílek, Josef; Podolka, Luboš; Karková, Monika (2016-01-01). "The Unique Construction of the Church of Hagia Irene in Istanbul for The Teaching of Byzantine Architecture". Procedia Engineering. 161: 1745–1750. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.770. ISSN 1877-7058.

- ^ "Hagia Irene Museum Opened | Topkapı Palace Museum Official Web Site". muze.gen.tr . Retrieved 2018-eleven-22 .

- ^ a b Heinle & Schlaich 1996 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFHeinleSchlaich1996 (assist)

- ^ Cameron 2009 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFCameron2009 (help).

- ^ Meyendorff 1982 harvnb error: no target: CITEREFMeyendorff1982 (help).

- ^ Bordewich, Fergus Thou. "A Monumental Struggle to Preserve Hagia Sophia". Smithsonian . Retrieved 2018-eleven-22 .

- ^ Plachý, Jan; Musílek, Josef; Podolka, Luboš; Karková, Monika (2016-01-01). "Disorders of the Building and its Remediation - Hagia Sophia, Turkey the Virtually the Byzantine Building". Procedia Engineering science. 161: 2259–2264. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.825. ISSN 1877-7058.

- ^ Cohen, Andrew (2011). "Compages in Religion: The History of the Hagia Sophia and Proposals For Returning It To Worship". FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. DOI: 10.25148/etd.FI14060867: two–3.

- ^ "Ayasofya Müzesi |". muze.gen.tr/ (in Turkish). Retrieved 2018-eleven-22 .

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Byzantine Art". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Further reading [edit]

- Bogdanovic, Jelena. "The Framing of Sacred Space: The Awning and the Byzantine Church building", New York: Oxford University Press, 2017. ISBN 0190465182.

- Ćurčić, Slobodan (1979). Gračanica: King Milutin's Church and Its Place in Late Byzantine Architecture. Pennsylvania Country Academy Press. ISBN9780271002187.

- Fletcher, Banister; Cruickshank, Dan, Sir Banister Fletcher'southward a History of Architecture, Architectural Printing, 20th edition, 1996 (first published 1896). ISBN 0-7506-2267-9. Cf. Part Two, Affiliate 11.

- Mango, Cyril, Byzantine Architecture (London, 1985; Electa, Rizzoli).

- Ousterhout, Robert; Master Builders of Byzantium, Princeton University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-691-00535-iv.

External links [edit]

- Overview of Byzantine compages in Constantinople

- The temples of the new religion

- Christianization of the ancient temples

- Photographs and Plans of Byzantine Compages in Turkey

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byzantine_architecture

0 Response to "Is the Most Elaborate Church of the Golden Age of Byzantine Art"

Post a Comment